Is all the hype about Leïla Slimani’s novel ‘Chanson Douce’ (‘Lullaby’) justifiable?

“Le bébé est mort. Il a suffi de quelques seconds. Le médecin a assure qu’il n’avait pas souffert….La petite, elle, etait encore vivante quand les secours son arrivés. Elle s’est battu comme un fauve. On a retrouvé des traces de lutte, des morceaux de peau sous ses ongles mous…Dans l’ambulance qui la trasportait à l’hôpital, elle était agitée, secouée de convulsions…Ses poumons étaient perforés et sat ête avait violemment heurté la commode bleue.”

“The baby is dead. It took only a few seconds. The doctor said he didn’t suffer… The little girl was still alive when the ambulance arrived. She fought like a wild animal. Traces of a fight have been found, pieces of skin under her soft nails . . . On the way to the hospital, she was agitated, her body shaken by convulsions. . . Her lungs had been punctured, her head smashed violently against the blue chest of drawers.”

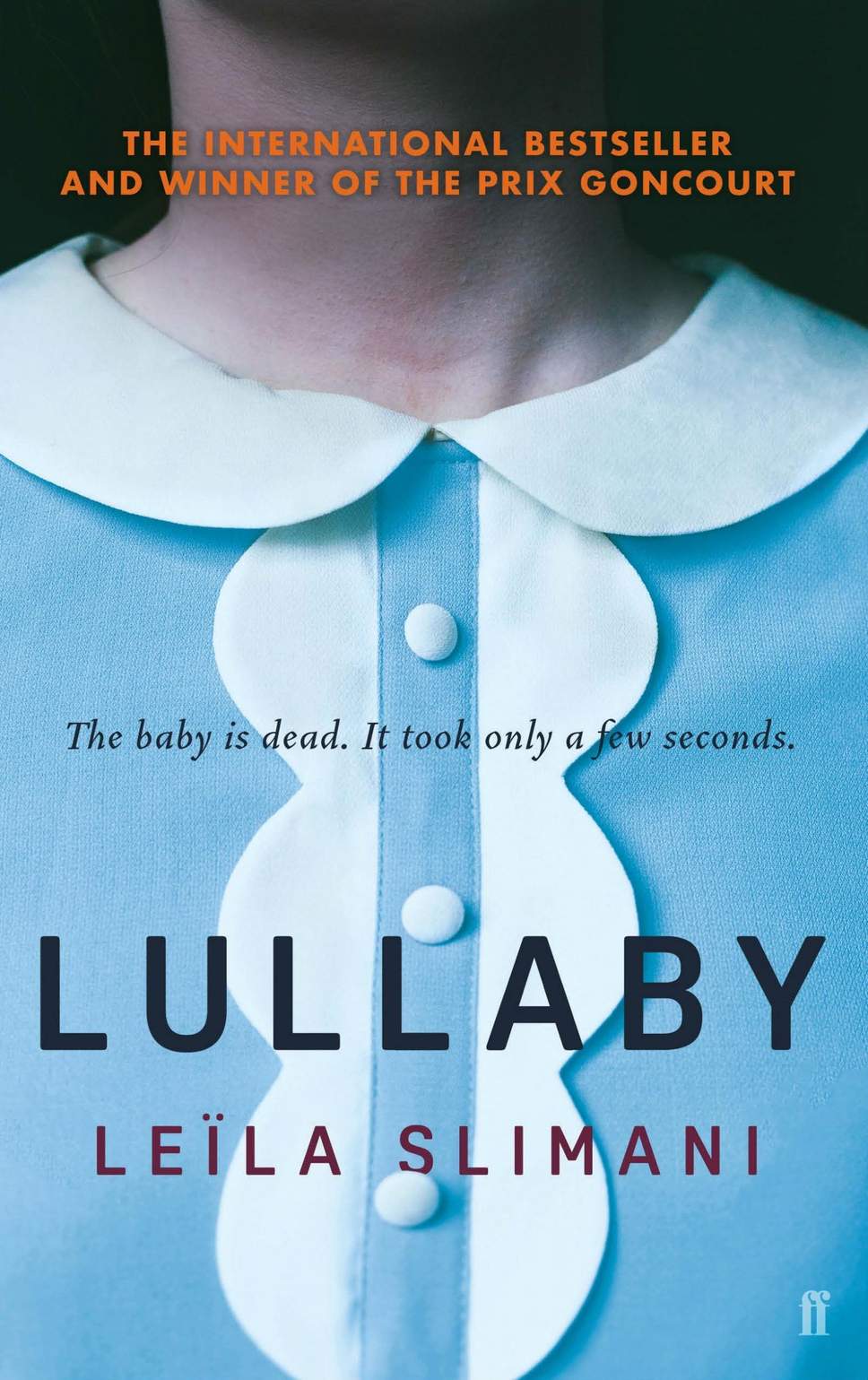

This strong and revealing incipit belongs to Leïla Slimani’s novel ‘Chanson Douce’, released not long ago in England with the title ‘Lullaby’, and in America under the less appealing – but for sure more effective in terms of marketing purposes – ‘The Perfect Nanny’. The title of the Italian version is ‘Ninna Nanna’. I read the novel in its original language, French, to have a first-hand experience of Slimani’s essential, neat and sharp prose, which – some critics said – had partly suffered with the English/American renditions of the book.

For this novel, Slimani, 36, a Franco-Maroccan writer and journalist, was awarded the ‘Prix Goncourt 2016’, which in France is given to ‘the best and most imaginative prose work of the year’. Ever since its release, the book has taken France by storm. And it has subsequently received rave reviews from various English and American magazines.

Allow me now a brief digression, before returning to Slimani’s work.

Remember one of the most famous novel openings “Aujourd’hui, maman est morte” (‘Maman died today’) by Albert Camus, ‘L’étranger’ (The Stranger)? I wonder if in Slimani’s “Le bébé est mort”– a statement that immediately places death as something hanging over everything else in the novel – there was a wish to reconnect with Camus. In ‘The Stranger’, Camus’ main character, Meursault, is an outsider who lives for the moment. And yet, even after his detached acknowledgement of his mother’s death, there is a yearning for her love, a feeling that he was unable to express when she was alive. His mother’s death marks a passage: there will be a time with no more ‘today’. A killing takes place, and death comes back, closing the circle.

In ‘Chanson Douce’ Louise, the killer nanny, is also a solitary and – as it turns out –mentally disturbed character, whose only meaning of existence is her daily job, or namely the selfish possession of love dispensed by the children she is taking care of. It is a love she is afraid to lose, together with her job, as the children grow up. This fear will drive her to commit the most atrocious action. Both writers deal with tragedy (mother’s and children’s death) as something the reader has to reckon with immediately, deeply questioning the meaning of life.

Slimani’s book does not want to be a thriller, but rather a psychological novel that touches inconvenient but universal themes, like the difficulty for women to balance child rearing and career; the subsequent uneasy relationship of dependance between the mother and the child carer; class inequality; the desperation of poverty; repressed rage, and the unpredictable twists of the human mind.

What is told here is the simple ‘banality of evil’, as Slimani called it. This is an ‘unexceptional story’, inspired by a similar murder that took place in the USA in 2012. Even if, from the first lines, we become aware of what has happened, we immediately want to know ‘what’ has driven the nanny to kill the children she has so affectionately taken care of, what horrors lie hidden underneath her confident demeanour. Slimani’s novel is worth reading not only for her beautiful and concise prose, but also for the way in which the author is able, by using a third-person omniscient narrator, to slowly drop hints about the heart of darkness hidden behind Louise’ imperturbable behaviour. Slimani crafts Louise, and all the characters, through showing rather than telling. And we find ourselves glued to the page.

Louise is hired by Paul (a music producer) and Myriam, so that Myriam can resume her work as a lawyer after a few years spent as a full-time mum. Myriam, of north-African heritage, specifically chooses to hire a French woman, and this ‘inverted’ relationship does create tensions and a social divide. Nonetheless, Louise is very respected by her employers and loved by the children, cooks perfectly and cleans and scratches surfaces to the point, even, that her nails break and become bloody. Most importantly, she reaches maximum satisfaction in her job when she sees the others thrive.

Myriam is obviously very tense at the thought of leaving the kids in the hands of a nanny, even if she cannot bear with the routine of a stay-at-home mum anymore. After the family interviews Louise, the narrator tells us that “Elle a le regarde d’un femme qui peut tout entendre et tout pardoner. Son visage est comme une mer paisible, don’t personne ne pourrait soupçonner les abysses” (“She has the look of a woman who can understand everything and forgive anything. Her face is like a peaceful sea, of which no one could suspect the abyss”).

Very soon, we witness how the whole family fully depends on Louise. She is just too good to be true. Louise gains more space in the running of the family routine and even starts to sleep, from time to time, at her employers’ home. This matter is avoided during conversations, never clearly approved, but accepted. Myriam, while observing her children playing joyfully with Louise, has moments of reflections about the price to pay to gain her own personal freedom. She is aware of the fact that the moment we depend on the others, and we lead a life that does not belong to us, we’re no longer free.

More clues are added to the plot and one day, while playing hide and seek with the children, Louise decides not to come out of her hiding place. The children become distressed and desperate while “elle les regarde comme o étudie l’agonie du poisson au peine pêché, les ouïes en sang, le corps secoué de convulsions” (“she watches them as if she’s studying the death throes of a fish she’s just caught, its gills bleeding, its body shaken by spasms”).

As we get to know more about Louise’s personal life and her past, we witness anger, rage and repression, a failed relationship with her own daughter Stephanie, who “pourrait être morte” (“could be dead”), the debts left by her dead husband, the rent to pay, her desire for a life where she can have “les moyens de tout avoir” (“The means for owning anything”), her loneliness and subsequent dependence on Myriam’s family as the most attainable source that gives a meaning to her life. Despite that, she feels hatred, a hatred that absorbs and destroys all. She’s haunted “par l’impression d’avoir trop vu, trop entendu de l’intimité des autres, d’une intimité à laquelle elle n’a jamais eu droit.” (“by the impression of having seen too much, of knowing other people’s intimacy, an intimacy to which she has never been entitled”).

There is an episode that – in all its morbidity – took me back to the strong imagery of Han Kang’s ‘The Vegetarian’ when all the meat, taken out of the freezer by Yeong-Hye, the main character, is scattered on the kitchen floor. One night, Myriam comes back from work. Louise greets her in a rush and dashes out of the house, an uncommon behaviour. Once in the kitchen, Myriam notices a chicken carcass on a chopping board, in the middle of the table. The carcass is shiny, with no trace of meat on it. “Il n’y a plus de viande, plus d’organes, rien de putrescible sur ce squelette, et pourtant, il semble à Myriam que c’est une charogne, un immonde cadaver qui continue de pourrir sous ses yeaux, là, dans sa cuisine.” (“There is no more meat, no more organs, nothing putrescible on this skeleton, and yet, it seems to Myriam that it is a carrion, a filthy cadaver that continues to rot under her eyes, there, in her kitchen”). Myriam had thrown away that chicken the same morning,because it had a bad smell,and it lay at the bottom of the garbage bin. And now the carcass is there, smelling of almond soap, instead. “Louise l’a lavée à grand eau, elle l’a nettoyée et elle l’a posée là comme une vengeance, comme un totem maléfique.” (“Louise washed it with a lot of water, cleaned it up and put it there like a sign of vengeance, like an evil totem”). Mila, Myriam’s daughter, excitedly tells the story to her mum, and laughs: with her brother, she has eaten the cooked chicken with her fingers, drinking lots of Fanta with it – as suggested by Louise – because the meat was too dry.

At this point, any parent should become absolutely vexed with the nanny, and kick her away. In fact, Myriam and Paul are making plans in this regard, but they always hesitate, never addressing any thorny matters with her. Sometimes it’s easier not to disturb the order of things just for sake of enjoying the privilege that comes with it.

Louise has one last obsession that will further push her to commit the heinous act even if, in my opinion, it is not that convincing as the main cause of the killing. Clearly, what has changed Louise from the perfect nanny to a horrible murderer is a build up of different situations and events.

As Slimani says in an interview with ‘The Newyorker’, “That animal part of us, it’s the most interesting part. It’s everything that has to do with drives, with things we can’t stop ourselves from doing, with all the spaces where we’re unable to reason with ourselves. It has its dark side, but there’s a luminous side, too, which is the fact that we’re just another species of animal.”

Paola Caronni